The most costly of all follies is to believe passionately in the palpably not true. - H.L. Mencken

Colleagues,

The other day I was reading an article from the

July 2011 edition of the Journal

Of Military History - "Some Myths of World War II", by

Gerhard Weinberg - when one of the passages leapt out at me. I'll cite it

in its entirety for you in a moment, but I wanted to explain first what it was

that had caught my eye.

As those of you who read a line or two into these

missives before pressing the delete key have no doubt noticed, I'm a strong

proponent of evidence as the core and foundation of science. Evidence,

I've argued in the past, plays the key role in every step in a rigorous

scientific endeavour. The first step in science - observation - involves

noticing some sort of data, recording it, and wondering what caused it.

The second step, hypothesization, requires coming up with a thesis that

explains and is consistent with one's initial observations. The third

step, experimentation, is an organized search for more evidence - especially

evidence that tends to undermine your hypothesis; and the fourth, synthesis,

requires the scientist to adapt his hypothesis so that it explains and is

consistent with not only the original observed evidence, but also all of the

evidence garnered through research and experimentation. This last

criterion is key to the scientific method: if one's hypothesis is not

consistent with observed data, it must be changed; and if it cannot be changed

to account for observations, it must be discarded. Science is like

evolution in that regard; only the fittest hypotheses survive the remorseless

winnowing process, and progress requires enormous amounts of time, and enormous

amounts of death. The graveyards of science are littered with extinct

theories.

But there's a fifth stage to science, one that

tends to be overlooked because it's technically not part of the "holy

quaternity" I've outlined above. The fifth stage is communicating

one's conclusions - not only to one's fellow seekers-of-fact, but also to those

on whose behalf one's efforts are engaged. This stage requires telling

the whole story of the endeavour, from start to finish, including all of the

errors and pitfalls. Publicizing one's misapprehensions and mistakes is a

scientific duty, for two reasons: first, because it improves the efficiency of

science by helping one's colleagues avoid the errors of observation and

analysis that you've already made (in army terms, "There's no

substitute for recce"); but more importantly, because total disclosure of

data and methods, and frank, transparent discussion of errors of fact and

judgement, are what give science its reliability and rigour. Transparency

and disclosure are the keystone of the scientific method, and are the reason

that science works - and the reason, I might add, that science has produced

steady progress since the Enlightenment, and has come to be trusted as

the only reliable means of understanding the natural world.

The thing is, disclosure of data and methods,

and frank discussion of errors of fact and judgement, might be strengths in the

scientific field, but in other fields of endeavour, they are often interpreted

as weaknesses. In a competitive business environment, for example,

disclosure of data and methods makes it easier for competitors to appropriate

or undermine your ideas. In such a cut-throat atmosphere, the individual

who conceals his activities, who refuses to discuss with colleagues (whom he

likely views as competitors) what he is doing, and how, and why, will

enjoy a comparative advantage vis-à

-vis those who are more open about their data, methods and

conclusions. As for discussion of errors of fact and judgement, in a

non-scientific atmosphere, the admission that one has made errors in

experimental design or in data collection, or the confession that one may have

misinterpreted observations or the results of an experiment, may be taken as a

sign of incompetence or lack of ability, rather than as an indication of the

type of honest transparency that is the hallmark of good science.

Acknowledgement of error, of course, is also

key to correcting an erring course of action - and this is true in every area

of activity in life, not merely in science. The first step, as they

say, is admitting that you have a problem - and this leads me

back to the citation from the article that prompted this line of thought

in the first place. In the article I mentioned above, Weinberg - a

distinguished scholar who has been writing about the Second World War for the

better part of 70 years - discusses a wide variety of some of the

"myths" about some of the well-known leaders of World War II.

When he comes to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, one of his more trenchant questions

pertains to why the famous naval commander, in preparing for the pre-emptive

attack on Pearl Harbour, was "so absolutely insistent on a

project with defects that were so readily foreseeable." Why, for

example, would you attack a fleet in a shallow, mud-bottomed harbour, where

damaged vessels could be so easily raised and repaired (18 of the 21 ships

"severely damaged" at Pearl Harbour eventually returned to

service)? Weinberg suggests that it may have been just as well for

Yamamoto's peace of mind that he was dead by the time of the battle of Surigao

Strait in October 1944, "when a substantial portion of the Japanese Navy

was demolished by six American battleships of which two had allegedly been sunk

and three had been badly damaged" three years earlier at Pearl Harbour.

Weinberg speculates that Yamamoto may have been so "personally

invested" in his tactical plan for the Pearl Harbour attack that he was

"simply unable and unwilling to analyze the matter objectively":

There is an intriguing aspect of the

last paper exercise of the plan that he conducted in September 1941, about

a month before the naval staff in Tokyo finally agreed to his demand that his

plan replace theirs. In that exercise,

it was determined that among other American ships sunk at their moorings would

be the aircraft carriers including the Yorktown. Not a single officer in the room had the

moral courage to say, “But your Excellency, how can we sink the ‘Yorktown’ in

Pearl Harbor when we know that it is with the American fleet in the

Atlantic?” None of these officers lacked

physical courage: they were all prepared to die for the Emperor, and many of

them did. But none had the backbone to

challenge a commander whose mind was so firmly made up that none dared prize it

open with a touch of reality.[Note A]

Where do we lay the blame for this error of

fact? On Yamamoto, for coming up with a scenario whose fundamental

assumptions were known to be wrong? On his subordinates, who accepted

those assumptions, knowing them to be wrong? Remember, this was not a

matter of a difference of opinion between experts; it wasn't a question of

differing interpretations of equivocal results. Nor was this a notional,

peace-time exercise; this was an exercise that took place in the work-up stage

of what was intended to be the very definition of a critical strategic

operation - a knock-out blow that would curtail the ability of the US to

interfere with Japan's plans for the Pacific. In such circumstances, one

would think that accuracy of data would be at a premium, and that fundamental

errors of fact would be corrected as soon as they were noticed. But this

didn't happen. This is a very telling anecdote, and Weinberg distils

from it a devastatingly important observation: that men who had no fear of

death, and who would (and did) fight to their last breath, nonetheless

somehow lacked the moral courage to disagree with their superior on a matter of

indisputable fact: that the exercise scenario did not reflect the real world. Where the USS Yorktown actually was (it

was conducting neutrality patrols between Bermuda and Newfoundland throughout

the summer and autumn of 1941) was in fact very important -

and what is more, Japanese intelligence had that information. Yet no one stepped up to correct the

scenario. No one challenged the planning

assumptions when actual data showed those assumptions to

be wrong.

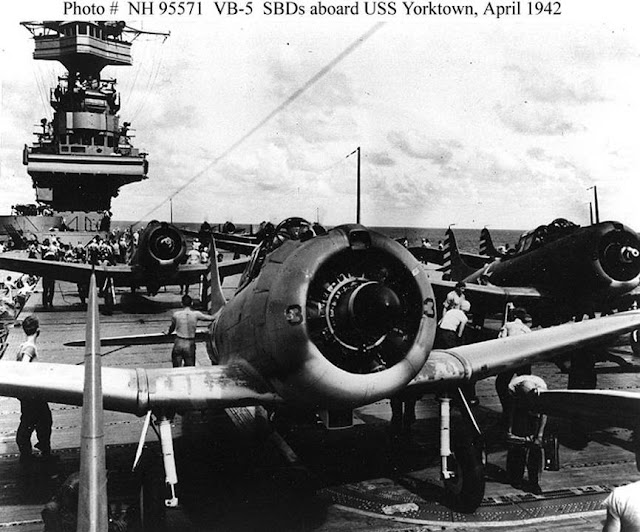

Yorktown's location should have mattered to

Yamamoto. When the Japanese Navy struck Pearl Harbour on 7 December

1941, USS Yorktown was in port in Norfolk, Virginia. She left Norfolk on

16 December, and was in San Diego by 30 December. She was later involved

in launching the Smiley raids against the Marshall Islands. Her air

wing accounted for numerous Japanese warships and landing craft at the Battle

of the Coral Sea.

She was also at Midway, where her air wing

destroyed the Japanese carriers Soryu and Hiryu, the latter while flying

from USS Enterprise after Yorktown was disabled.

In less than six months,

that one ship accounted for 25% of Japan's carrier strength.

Where she was in the fall of 1941 mattered, because none of these

things would have happened if Yorktown had been badly damaged or sunk at

Pearl Harbour.

Why did Yamamoto's exercise plan assume that

Yorktown would be among the ships tied up in Battleship Row, when he knew it

was on the other side of the world? Why did no one challenge the

scenario? It's easy, as many historians have done (and not without

justification) to write off staff subservience to a commander as the inevitable

consequence of centuries of deification of the Emperor, the warrior

philosophy of bushido, and decades of Imperial Japanese militarism.

But how can we simultaneously accept that such an organizational

entity is at once both a dangerously innovative and adaptive enemy, and yet

so rigidly hierarchical that the thought processes of the senior

leadership are utterly impervious even to objective fact? The two

qualities, it seems to me, are mutually exclusive. One cannot be

both intellectually flexible and intellectually hidebound.

Yamamoto's refusal to incorporate known facts

into his exercise plan, and his subordinates' refusal to insist on their

incorporation, resulted in flawed planning assumptions. Over time, the

impact of these flawed assumptions came back to bite them in their collective

posteriors, in some cases personally. But they bit the Empire, too.

In her 1984 treatise on folly, Barbara Tuchman spends most of her time

castigating governmental elites for long-term, dogged pursuit of

policy contrary to the interests of the polity being governed; but she

also investigates the sources of folly. One of these, upon which she

elaborates with characteristic rhetorical verve, is the refusal of those in

positions of authority to incorporate new information, including changes in objective

facts, into their plans:

Wooden-headedness, the source of

self-deception, is a factor that plays a remarkably large role in

government. It consists in assessing a

situation in terms of preconceived fixed notions while ignoring or rejecting any

contrary signs. It is acting according

to wish while not allowing oneself to be deflected by the facts. It is epitomized in a historian’s statement

about Phillip II of Spain, the surpassing wooden-head of all sovereigns: ‘No

experience of the failure of his policy could shake his belief in its essential

excellence’. [Note B]

Or to put it more simply, as economist John

Maynard Keynes is reputed to have said when he was criticized for

changing his position on monetary policy during the Great Depression,

"When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?"

I could go on about this at great length,

citing innumerable examples (as I expect we all could) but I thought that just

one would do - surprisingly, from the field of climate science. In its

4th Assessment Report, issued in 2007, the IPCC claimed that Himalayan glaciers

were receding faster than glaciers anywhere else in the world, and that they

were likely to "disappear altogether by 2035 if not sooner." In

2010, the IPCC researchers who wrote that part of the report confessed that

they had based it on a news story in the New Scientist, published in 1999

and derived from an interview with an Indian researcher - who, upon being

contacted, stated that his glacial melt estimates were based on speculation,

rather than formal research. Now, according to new, peer-reviewed

research based on the results of satellite interferometry - i.e., measured data

rather than speculation - the actual measured ice loss from glaciers

worldwide is "much less" than has previously been estimated.

As for the Himalayas - well, it turns out they

haven't lost any ice mass at all for the past ten years.(Note C) As one

of the researchers put it, the ice loss from high mountain Asia was found to be

"not significantly different from zero."

Amongst other things, this might explain why

satellite measurements show that sea levels, far from rising (as the IPCC said

they would), have been stable for a decade, and now appear

to be declining. After all, the amount of Aitch-Two-Oh on Earth

is finite, so if the glaciers aren't melting, that would explain why the sea

levels aren't rising, non?

Remember, according to the IPCC AR4, under the

most optimistic scenario for GHG reductions (i.e., massive reductions in GHG

emissions, which certainly haven't happened), sea level would increase by 18-38

cm by the year 2099, which equates to an absolute minimum increase of 1.8 mm

per year (see the AR4 SPM, pp 7-8, Figure SPM.5 and Table

SPM.1). According to the IPCC's model projections, over the

past decade sea levels should have risen by at least 1.8 cm (on the above

chart, that's half the Y-axis, which is 35 mm from top to bottom. In

other words, the right hand end of the curve should be well above the top of

the chart). But according to the most sensitive instruments we've yet

devised, sea levels haven't risen at all over the past decade, and for the past

three years have been steadily falling. This isn't a model output;

it's not a theory. Like the non-melting of Himalayan glacier ice, it's

observed data.

Why point this out? Well, our current

suite of planning assumptions state that, amongst other things, Himalayan

glaciers (along with glaciers all over the world) are melting, and that as a

consequence, sea levels are rising. "Rising sea levels and melting

glaciers are expected to increase the possibility of land loss and, owing to

saline incursions and contamination, reduce access to fresh water resources,

which will in turn affect agricultural productivity." (Note D) Those assumptions

were based on secondary source analysis - basically, the IPCC reports, which

were themselves largely based on secondary source analysis (and, as shown

above, occasionally on sources with no basis in empirical

data) - but when verified against primary research and

measured data, they are demonstrably wrong. In

essence, stating that defence planning and operations are likely to

be impacted by "rising sea levels" or "melting

glaciers" is precisely as accurate as Yamamoto planning to sink the USS

Yorktown at Pearl Harbour when everyone knew that it was cruising the Atlantic.

A big part of folly consists of ignoring facts

that don't conform to one's preconceptions. Actual planning or

policy decisions may be above our pay grade as mere scientists - but what isn't

above our pay grade is our moral and professional obligation to point

out the facts, and to remind those who pay us that when facts conflict with

theories or assumptions, it's the theories or assumptions that have to

change.

So when we see people basing important decisions on inflammatory rhetoric from news reports – for example, a CBC piece hyping an already-hyped “scientific” study arguing that sea level rises have been “underestimated”...

Some scientists at an international symposium in Vancouver warn most estimates for a rise in the sea level are too conservative and several B.C. communities will be vulnerable to flooding unless drastic action is taken.

The gathering of the American Association for the Advancement of Science heard Sunday the sea level could rise by as little as 30 centimetres or as much as one metre in the next century.

But SFU geology professor John Clague, who studies the effect of the rising sea on the B.C. coast, says a rise of about one metre is more likely.

...it behooves us, as scientists, to look at the data. And what do the data say in this case? Well,

they say that over the past century, the sea level at Vancouver hasn’t risen

at all.

The average sea level at Vancouver for the past century has been 7100 mm. If, as the above-cited report claims, Vancouver's sea level had risen by 30 cm, then the average at the right-hand end of the screen should be 7400 mm, close to the top of that chart. But it's not; it's still 7100 mm. The trend is flat. Absolutely flat.

So as it turns out, according to one of the supposed "key indicators" of anthropogenic climate change is concerned, nothing is happening. If sea levels are the USS Yorktown, the Yorktown isn't at Pearl Harbour at all. She's nowhere near Hawaii. She's not even in the Pacific; she's on the other side of the world, off cruising the Atlantic. But nobody has the moral courage to say so. All of the planning assumptions in use today are firmly fixated on the idea that the Yorktown is tied up at Pearl.

Well, assume away, folks. But no matter how many dive bombers you send to Battleship Row, you are simply not going to find and sink the Yorktown, because the facts don't give a tinker's damn about your assumptions. She is just...not...there.

Of course, finding out the facts – the observed

data – is only the first part of our duty as scientists. The next and even more

important part is...what do we do

with them? Unlike Yamamoto's juniors, whose ethical code

condemned them to obedience, silence and eventually death, our ethical code

requires us to sound the tocsin - to speak up when decisions are being made on

a basis of assumptions that are provably flawed. And more than that; we

shouldn't just be reporting contrarian evidence when we stumble across it,

we should be actively looking

for it. A scientific theory can never be conclusively proved; it can

only be disproved, and it only takes a single inexplicable fact to disprove

it. Competent scientists, therefore, hunt for facts to disprove their

theories - because identifying and reconciling potential disproofs is

the only legitimate way to strengthen an hypothesis. We have to look for

things that tend to undermine the assumptions that are being used as

the foundation for so much time, effort, and expenditure, because that's

the only way to test whether the assumptions are still valid. If we don't do

that - if we simply accept the assumptions that we are handed instead of

examining them to see whether they correspond to known data, and challenging

them if they don't - then we're not doing the one thing

that we're being paid to do that makes us different from the vast

swaths of non-scientists that surround us.

Playing the stoic samurai when important,

enduring, expensive and potentially life-threatening decisions are

being based on demonstrably flawed assumptions is fine if your career plan

involves slamming your modified Zero into the side of a

battleship and calling it a day. But if you'd prefer to see your team come out

on top, sometimes you've got to call BS. That should be easier for

scientists than it is for most folks, because it's not just what we're paid to do;

it's our professional and ethical obligation to speak out for the

results of rigorous analysis based on empirical fact.

So when you

think about it, "Where's the Yorktown?" is in many ways the

defining question that we've all got to ask

ourselves: is she where our assumptions, our doctrine, last year's exercise

plan, the conventional wisdom, the pseudo-scientific flavour of the month, or

"the boss" says she ought to be?

Or is she where, based on observed data, we know her to be?

How we answer that question when it's posed to

us determines whether we are scientists...or something else.

Cheers,

//Don//

Post Scriptum

Today, the USS Yorktown is in 3

miles of water off of Midway Island. She was rediscovered by Robert

Ballard on 19 May 1998, 56 years after she was lost.

For the record, the average sea level at Midway Atoll has increased by about 5 cm since 1947 (65 years). This amounts to 0.74 mm per year, which is less than 1/4 the alleged minimum rate of sea level increase expected due to "climate change", according to the IPCC. And even that tiny increase is due not to "anthropogenic climate change", but rather to isostatic adjustment as the weight of the coral atoll depresses the Earth's crust, and - according to this recent study - to tidal surges associated with storminess that correlates with the increasing Pacific Decadal Oscillation over the past sixty years.

It's all about the evidence, friends. You either have it or you don't. And if you have it, you either try to explain it - like a real scientist - or you ignore it. Ignoring the evidence didn't turn out well at all for Yamamoto, the Imperial Japanese Navy, or in the long run, Imperial Japan.

Notes

Photos courtesy the US Navy History and Heritage Command.

A) Gerhard L. Weinberg, “Some Myths of World War II – The 2011 George C. Marshall Lecture in Military History”, Journal of Military History 75 (July 2011), 716.

B) Barbara Tuchman, The March of Folly from Troy to Vietnam (New York: Ballantine Books, 1984), 7.

C) http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/feb/08/glaciers-mountains

D) The Future Security Environment 2008-2030 - Part 1: Current and Emerging Trends, 36.